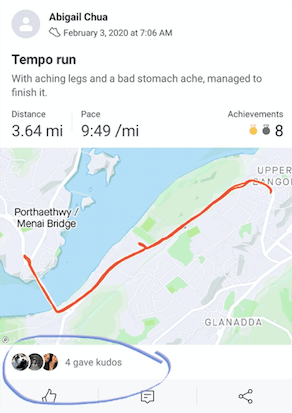

Its seven in the morning, its dark out and its freezing cold, close to zero degrees outside. I yawn as I put on my gear and go out running, only to be plagued by a horrible stomach ache as I crossed Menai Bridge that lasted me the whole run back home. On the bright side, that allowed me to run much faster then I normally would on a tempo run, my brother even gawking at me at how I managed to increase by speed from 8km per hour to 12km per hour.

It’s the third week of the semester, with 14 weeks left (if my maths is correct) until the marathon, with just a little under 4 weeks until the Anglesea half marathon and I’m beginning to feel very worn out, both mentally and physically. My body aches, my mind is screaming that I need some time out and stay at home, reflect on whether I am actually mad trying to do this.

Let’s start off with the main reason why I wanted to do this in the first place : I wanted to be able to tell people I did a marathon, to be able to at least have done something my friends or people I know haven’t done before, to stand out from the crowd. This is what is called extrinsic motivation , where a person does something to get a distinct reward.

In my case, I want acceptance from people, for people to acknowledge I might be able to do something. I have had a history of having low self esteem and always having the need for people to accept me by trying to do things that I normally wouldn’t have done. Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, and Schimel (2004) suggested terror management theory, where a person yearns for self esteem to protect themselves from a world that is dangerous and they need everything in their power to survive in it. Essentially, that is how I feel; having to survive in a world that demands the survival of the fittest, leading to me trying to go above and beyond to stand out from the crowd. Crocker and Knight (2005) pointed out that by basing out lives on contingencies of self worth, this may lead to detrimental consequences such as intense emotion such as self blame when not being able to achieve a goal, poorer health and taking risky behaviours. This could explain why at certain times, even though I might feel my legs about to break, with a storm brewing in the distance or having cramps, I still try to push myself to the limit even though I know there is a risk of me getting injured (or just feeling like crap).

However, that doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy running. I do enjoy running, which means my actions are intrinsically motivated to some degree, where I do have a bit of curiosity in trying to see my limits in a sport I never tried out seriously before. Covington and Mueller (2001) describe the reward paradigm of intrinsic motivation as finding joy in achieving something out of the ordinary and engaging in it because they want to. For me, I find running fun since I did some running in school and with my parents and now that I have the chance to do this module so few people manage to get into, I want to see if I can do it and if I can somehow change my life in the process as I go along with the training and classes.

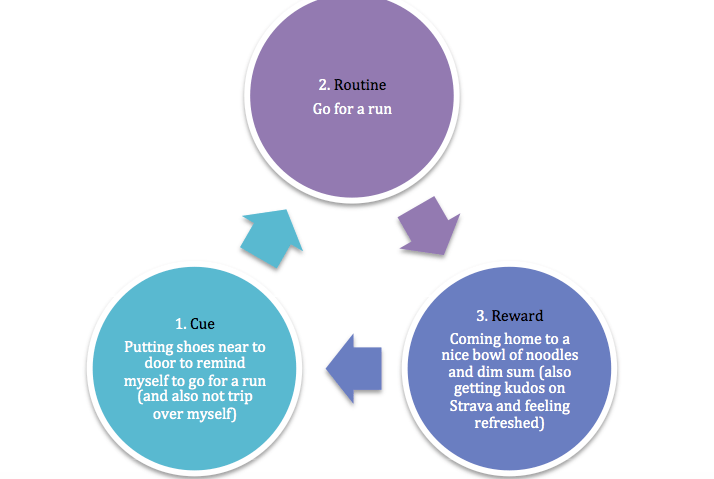

So what has class taught me about how to motivate myself? First thing I have to do is try and create a habit of running for myself. A habit is an action that is triggered by automatically to a cue associated with a person’s routine or performance. It does take time to form a habit, as shown in a study by Lally, Van Jaarsveld, Potts and Wardle (2010) where it took from 18 days even up to 284 days for a habit to form, although missing a few days did not really affect whether the habit would be broken or not. Aarts and Dijksterhuis (2000) suggested that by creating an environment where the habit would be easier to perform, it would result in the habit being carried out more easily. For running, if my running shoes were to be put close to the door, it would make it easier for me to access my shoes for running first thing in the morning.

With these thoughts in mind, here is a little diagram I made for my plan to actually put all of this together and how to create a running habit.

Also, its also a good thing to reward yourself once in a while when you do something (like running 14km on a Saturday morning when you can be asleep). Food is a good motivator for me; I like to have a nice bowl of Spicy Korean Noodles with some dim sum and eggs for breakfast once I finish my run. Its also nice to have people giving ‘kudos’ on your Strava whenever you do a run; it makes you feel good (especially one where you had a bad stomachache and thought you were seriously going to spill your guts on the road).

However, what happens if these rewards stop coming in? Would I still want to run if I run out of noodles to eat, if no one gives me ‘kudos’ on Strava because they got bored of following my progress? Or, what happens if I keep getting these rewards every week? Will they still serve as a good motivator to me or might they actually lead to me not wanting to run even more?

This phenomenon, known as the hedonic treadmill happens when a person grows accustomed to the rewards they received to the point that it becomes normal to them. This means that if I keep eating the food I use as a reward every time I go for a run for a long period of time, it may eventually reach a point where I don’t even feel rewarded eating it and this might demotivate me . However, it is important to distinguish between two kinds of rewards that come into play in this concept; hedonia and eudaimonia. Waterman (2007) described hedonia as pleasure and doing something fun (positive effect) while eudaimonia is all about trying to see the bigger picture and trying to achieve something more (learning from the experience). In Turban and Yan’s (2016) study, both have been shown to be important in the workplace, where people with more hedonistic values tended to love their job more while people with higher eudaimonia levels exhibit attitudes that may help them in the long run of their career.

So how does it apply to my running? In terms of looking at it from a eudaemonic perspective, I should see the running as a way for me to become healthier in the long run, maybe have something interesting to say to interviewers in the future and to also be able to end my undergraduate life on a high note. From the hedonistic perspective, it isn’t all the time I get to run a marathon for a module with other people so I should take this opportunity to just have fun running it and enjoying myself. I don’t know if I may ever have this opportunity in the future so I should just enjoy the moment and have fun.

Let’s hope this plan comes into play and that I would be able to get myself motivated into running once more (while I am running three to four times a week, I feel I’m not doing enough).

Until the next blog, peace out and please continue to watch and support me in my journey through this module.

References:

Aarts, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2000). Habits as knowledge structures: Automaticity in goal-directed behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(1), 53.

Covington, M. V., & Müeller, K. J. (2001). Intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation: An approach/avoidance reformulation. Educational psychology review, 13(2), 157-176.

Crocker, J., & Knight, K. M. (2005). Contingencies of self-worth. Current directions in psychological science, 14(4), 200-203.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2009). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. In The science of well-being (pp. 103-118). Springer, Dordrecht.

Gardner, B., Lally, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’and general practice. Br J Gen Pract, 62(605), 664-666.

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-overjustification-effect-2795386.

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European journal of social psychology, 40(6), 998-1009.

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the” overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 28(1), 129.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., & Schimel, J. (2004). Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological bulletin, 130(3), 435.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67.

Turban, D. B., & Yan, W. (2016). Relationship of eudaimonia and hedonia with work outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology.

Waterman, A. S. (2007). On the importance of distinguishing hedonia and eudaimonia when contemplating the hedonic treadmill.

Waterman, A. S. (2007). On the importance of distinguishing hedonia and eudaimonia when contemplating the hedonic treadmill.